It’s 1965. Students in army surplus jackets pass joints in their dorm while a wobbly Bob Dylan record plays. The war in Vietnam is escalating. Draft cards are arriving in mailboxes, friends and neighbours are disappearing. Among the Xeroxed anti-war leaflets and college textbooks, there’s a cheap, bright-red paperback being passed from hand to hand. It’s not assigned reading. It’s not even entirely legal. The book is The Lord of the Rings, and for reasons no professor quite understands yet, it’s become the sacred text of 1960s counterculture.

That pirated Tolkien paperbacks hit like a bomb in 60s campuses. The bootleg copy was printed due to a loophole in copyright law and quickly became a cult phenomenon, selling over 100,000 copies in 1965 alone. The biggest fans of the book seemed to be hippies, protesters and rockstars. It makes sense when you look at the context.

By the mid-1960s, the American dream had soured. The machinery of progress had turned on its creators. Factories poisoned rivers. The government sent 18 year-olds to war. Inequality was everywhere. Popular culture gunned for lasers, L.E.D.s, fluorescent-lit office towers, nuclear power, push button phones, TV dinners and space rockets. In a world that seemed to be speeding toward annihilation, pre-industrial societies began to look like a refuge, maybe even a roadmap. The disenfranchised youth searched for progress in the past.

The Middle Ages, at least as reimagined by the 1960s, offered a pre-capitalist, enchanted world of communes and troubadours. Although we now stereotype the Middle Ages aesthetic as a sort of grey porridge full of nuns, this isn’t accurate. Historian Jacques Le Goff describes “big jewels inserted into the boards of book-bindings, glowing gold objects, brightly painted sculpture … and the coloured magic of stained glass.” Groovy. Unlike the sterile technocracy of the Cold War, this view of bygone times gave people something to be excited by. The Middle Ages offered craftsmanship, self-sufficiency, small-scale communities and a respect for herbal medicine (however you’ll interpret that). It became a framework to imagine a better future. With those foundations already in place, it made sense that The Lord of the Rings was a hit with hippies.

To outsiders, this fascination with elves and orcs might’ve seemed like childish evasion. But for many, Middle Earth felt eerily similar to America. Mordor was an industrial hellscape, perhaps staffed by the same sort of men drafting teenagers into Vietnam. The Ring, a corrupting force of pure power, became a stand-in for nuclear weapons, for imperialism, for the creeping fingers of the draft board. Gandalf seemed more trustworthy than any actual political figure. Even now, medieval fantasy often gets dismissed as escapism, but it provides a lens through which people can critique the present.

What followed was a cultural re-enchantment. The phrase FRODO LIVES began popping up in subway graffiti. Protestors wore pins saying GANDALF FOR PRESIDENT. Fantasy, once dismissed as juvenile, became swept up in revolution.

The Middle Ages, or at least a hallucinogenic approximation of them, were back. Tapestries decorated dorm walls, flutes replaced saxophones, and on the outskirts of Los Angeles, a former high school teacher was about to launch what would become one of the most enduring legacies of the movement: the Renaissance Faire.

The link between the Red Scare and Californians in codpieces selling turkey legs may seem tenuous, but the evolution was pretty organic. Phyllis Patterson had been teaching English and drama in LA during the 50s, a time when the McCarthy-era blacklist loomed over California’s creatives. Left-leaning writers, actors and teachers were being purged from public jobs. Restrictions were piling onto Patterson, controlling what she could teach, so she quit her job to start the first Ren Faire. Blacklisted creatives came together in an oak-filled valley to reenact a freer, weirder, and more communal past.

Here, among the jesters and maypoles, the counterculture found a place to imagine new forms of community, rooted firmly outside the reach of nationalism or Cold War conformity. Medievalism, in this light, wasn’t nostalgia. It was insurgency.

The costuming of the Faires drew from the well of the Pre-Raphaelites, a 19th-century British art movement that idolised the medieval world. You can also see it in the aesthetics the hippies chose to adopt. Instead of plucked hairlines and architectural hats, they went for something closer to a billowing-sleeved woodland sorceress. Gunne Sax, the clothing line launched by Jessica McClintock, found an eager audience among women who wanted to look like they might stumble into a forest glade to meet a unicorn.1

For men, dressing like a medieval bard was a protest against everything the Mad Men generation stood for, from their politics to their crew cuts. Fashion meant velvet jackets, embroidered shirts, beads and long, flowing hair. The gold standard was Donovan, a musician who often dressed like he ought to be crouching in a tree stump, or later Jimi Hendrix with his colourful scarves and satin bell sleeves.

Rock musicians of this era seemed enamoured with fantasy. Led Zeppelin dropped references to Mordor and Gollum (who steals Robert Plant’s girl in Ramble On). Marc Bolan of T. Rex posed looked a glam knight in a leather breastplate, singing about wizards, dragons, and cosmic love. There were rumours that the Beatles themselves once dreamed of starring in an adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, casting Paul as Frodo, Ringo as Sam, George as Gandalf, and John as Gollum.

But every mythic age has its twilight. Unlike the fantasy books it stemmed from, this aesthetic was destined for a sad, unceremonious ending. By the end of the late 70s, its shimmer had dimmed. The Vietnam War ground to a bitter and painful end, leaving its shell-shocked veterans to sleep on pavements. The dream of a countercultural revolution had largely dissipated into a haze of burnout, blowouts and disco. For many idealists, the enchanted world they’d imagined didn’t survive the morning after. The Shire hadn’t been saved. The dragons hadn’t been slain. The real world remained stubbornly modern, mechanised and unfair.

Even Frodo didn’t quite hold onto his status as an outlaw mascot. By the time the new millennium rolled around, bringing a Lord of the Rings film adaptation with it, Frodo came free with a Burger King combo meal. The sacred text of 1965 had become mass-market merch – Sideshow Collectibles, One Ring replicas, key chains and hobbit feet slippers. In the era of iPods and MySpace and early-internet memes (visualise a snowy owl with “O RLY?” pasted over it), a new incarnation of anti-war Frodo was being incubated. When the drums of war started again, so did the magic.

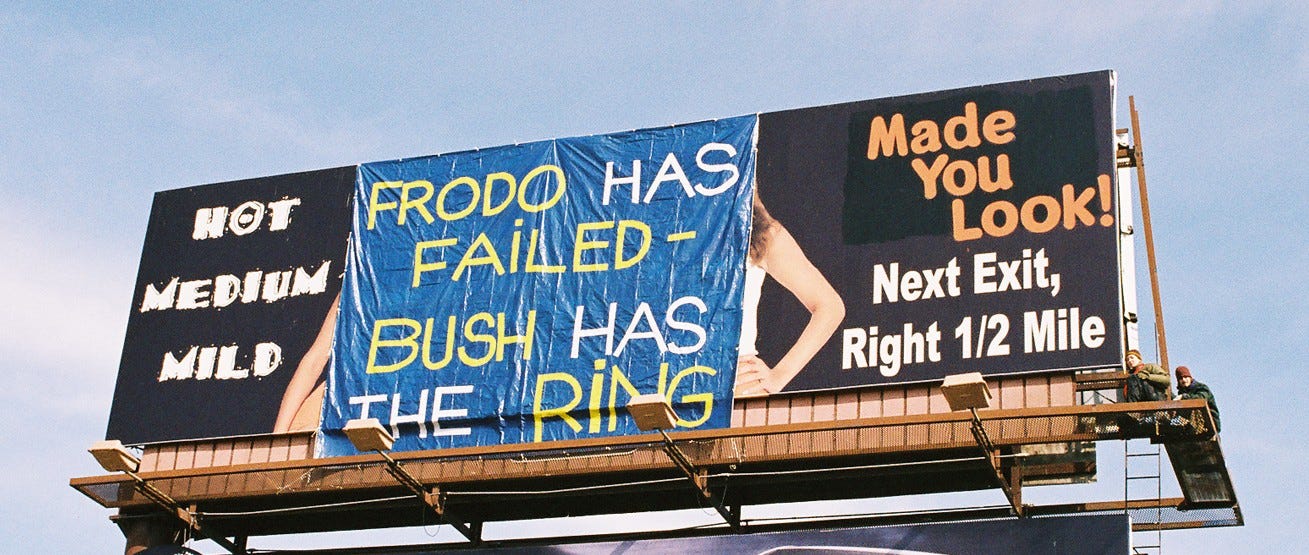

As U.S. troops deployed to Iraq in 2003, protestors once again took to the streets, just as they had in the late 1960s. There were candlelight vigils and acoustic guitars strumming under handmade banners. But this time, among the cardboard peace signs, a new twist on an old slogan emerged: “Frodo Has Failed: Bush Has the Ring.”

Originally circulated online with a photoshopped image of President George W. Bush wearing the One Ring, the phrase quickly spread to bumper stickers, T-shirts, and protest posters. The implication was chillingly clear: the forces of militarism and empire, once imagined as Sauron’s realm in Middle-earth, had re-emerged again in real life.

For many, the Iraq War felt like Vietnam all over again but by the 2000s, the mood was different. There was an extreme cynicism that hadn’t been there in 1968. The old counterculture had, in many ways, been absorbed into the mainstream. Peace symbols were now fashion statements. Hobbit quotes were printed on discount coffee mugs. For some, “Frodo Has Failed” wasn’t just a jab at Bush. It was an admission that the revolution hadn’t come. The world hadn’t changed. The Ring had just found a new bearer.

As depressing as that sounds, there’s something heartening about the endurance of fantasy as protest. When reality feels unbearable, fantasy becomes both sanctuary and sword. Fantasy so often deals with themes of revolution – corrupt kings, unfair distributions of power and unlikely heroes rising up against empires. It reminds us that the world can be remade, that darkness can be challenged and that resistance, however small or strange, still matters.

My favourite sources and further reading:

FROM ‘FRODO LIVES!’ TO ‘FRODO HAS FAILED’ On Popular Culture, The Lord of the Rings and Political Activism by Meghan Schalkwijk

Well Met: Renaissance Faires and the American Counterculture by Rachel Lee Rubin

Side note, I want a Gunne Sax dress so bad. The original 60-70s ones are fairly easy to find on Vinted and the like, but only if you have £200+ per dress. ModCloth revived the label a couple years back and they just did a collection with them a couple weeks back but it’s all a very specific shade of blue/green that reminds me of dentistry. Googling “Gunne Sax 1970s” makes me vibrate like a Chihuahua.

Wow, so fascinating! I had no idea that mid-century medieval went so deep. It makes a lot of sense though, especially since LOTR was written by Tolkien with heavy influences from his wartime experience depicting the horrors of WWI and touching on the bonds that were formed, creating hope.

“The link between the Red Scare and Californians in codpieces selling turkey legs may seem tenuous, but the evolution was pretty organic.” This made me laugh so hard. Wonderful piece! ❤️