Ten years ago, my classmate stood on a stage, an orange cupped in her hands. A local speaker had been invoked from the depths of some local church association to teach us about irreversible choices. Poised like a prophet before a sea of slouched teenagers, she set to work. Her metaphor of choice was the orange.

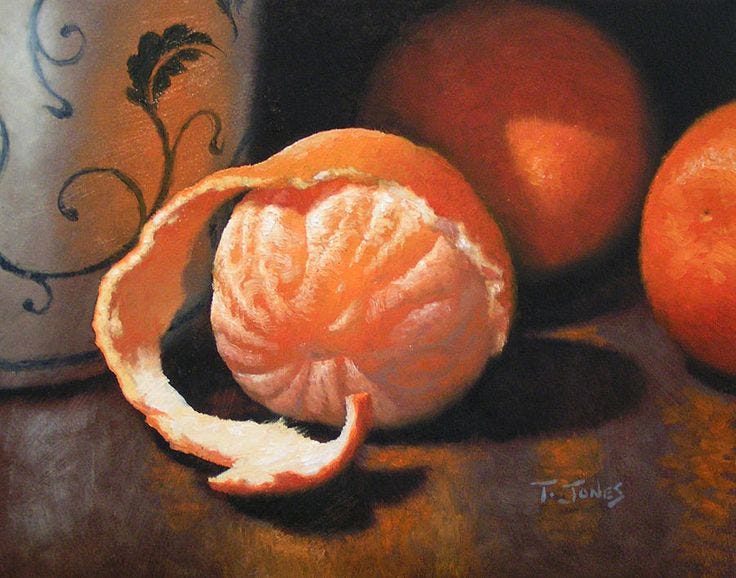

My classmate, chosen at random, dug her fingernails into the fruit’s dimpled skin. Under duress, she shredded the orange until it was naked, gorging chunks of flesh with her clumsy thumb. Juice pooled in the creases of her hands.

“There,” she said, presenting the dismantled segments to the speaker, balanced on her flat, sticky palm. “Is that it?”

“Yes,” the speaker replied, eyes gleaming in that Protestant way that signals a parable is about to rear its head. As the school hall filled with the smell of ruined orange, she nudged her red glasses up her nose. “Now unpeel it.” (She delivered that line like an anime lawyer.)

Her point was clear: in the act of transformation, you lose something that you might never be able to recover. You can’t unruin an orange. Don’t do anything you might regret.

My little pubescent eyes narrowed. A massive contrarian at 14 (I watched a lot of atheism videos), I was desperate to prove her wrong. Surely I could peel it with precision, a method that would leave the skin intact, ready to be stitched back together.

I got to work at lunch, fishing two clementines from my Tesco lunch bag. While my friends wove daisy chains and philosophised about The Vampire Dairies, I worked with the precision of a watchmaker. I peeled and re-peeled, tested and refined, nails lodging with pith. The grass had pressed my calves with swirling indents by the time I perfected my technique.

It was simple. You pierce your thumb into the citrus and unzip it round the equator. Carefully, you prise off the top and bottom poles until boom, the peel comes off in one tectonic plate.

Everyone peels an orange differently. Some tear at it with abandon, some strip it carefully, piece by piece. Others dissect it with surgical precision just in case any red-glasses parable fans try to make a point about irreversible choices.

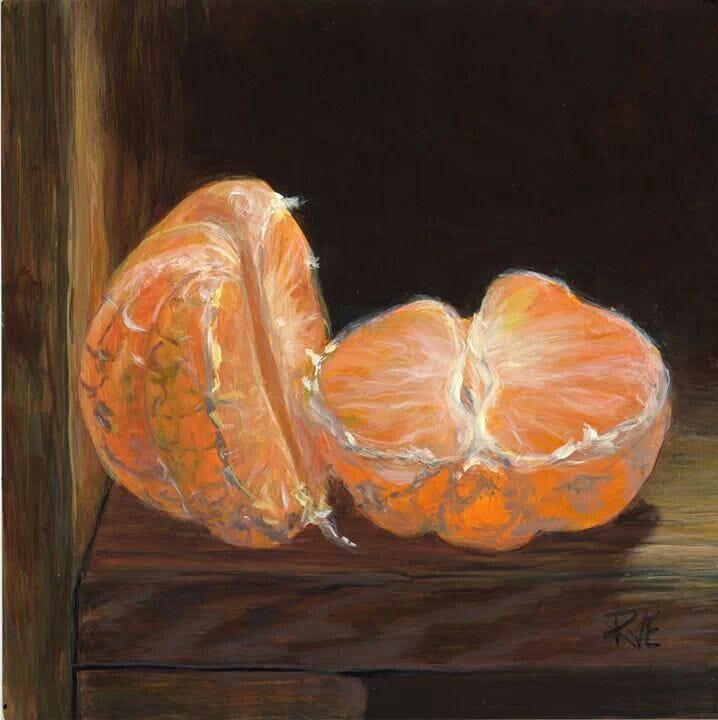

When you love someone, you learn their method, perhaps without realising. You might watch them roll it between their palms first, softening the skin, or slice through the peel with a knife. Their method becomes familiar, an unnoticed intimacy until one day, you find yourself peeling it just like they do.

Oranges have always known something about love. They are ripe (argh) for metaphor with their transformation from something whole and contained to something exposed and consumed. To enjoy them, they must be disrobed. Their segmentation means you can, perhaps should, share them.

Even the colour of the orange speaks to something primal about love. Before the English language first met the orange, people called that colour family “yellow-red”, or geoluhread. Once the fruit became known, so too did the word. The orange gave a name to something that had always been there, waiting to be perfectly defined.

The entire history of the orange is soaked in romance. During the crusades, the custom of entwining orange blossom’s into a bride’s hair came to Europe. “To gather orange blossoms” took the meaning “to seek a wife” and Queen Victoria was married crowned with an orange blossom headdress instead of a tiara.

In the medieval times, people would poke cloves and cinnamon into an orange as a plague remedy, and lovers would gift them to one another. I can’t imagine the joy of being a 12th-century scribe, skipping home with a stinky orange in your pocket, made with tender care by your lover Wynflaed.

The orange-gifting tradition persisted into the 18th century England, when people gifted each other oranges (as well as root ginger and pineapple) as part of their courtship rituals. A famous example of this comes from the Ladies of Llangollen, two upper-class Irish women of the time who defied convention to live together as wives. They knew the romance of an orange. The women “used oranges, cheese, strawberries, geese and figs as gestures of friendship and intimacy”.

I can only dream of the level of intimacy that might drive someone to gift her wife multiple geese. The orange, however, makes sense to me. Oranges invite touch, scent and taste in a way few other fruit do. They’re not torn like an apple or popped like a grape. The eating process is tactile, sensory, an act that requires engagement. You have to break the peel with your nails, sending a spray of fragrant citrus oil. The scent lingers on your fingers and tongue. If you’re close enough to someone, you can always tell when they’ve eaten an orange.

The poem Stolen Moments by Kim Addonizio uses oranges to convey how love and touch outlast their immediate experience. Cool against the skin, bursting on the tongue, it comes to represent sensuality.

What happened, happened once. So now it’s best

in memory – an orange he sliced: the skin

unbroken, then the knife, the chilled wedge

lifted to my mouth, his mouth, the thin

membrane between us, the exquisite orange,

tongue, orange, my nakedness and his,

the way he pushed me up against the fridge –

Now I get to feel his hands again, the kiss

that didn’t last, but sent some neural twin

flashing wildly through the cortex. Love’s

merciless, the way it travels in

and keeps emitting light. Beside the stove

we ate an orange. And there were purple flowers

on the table. And we still had hours.

Just like the orange, the poem is bittersweet. The passion it describes is edged with loss, a love that didn’t last but still leaves its imprint. Love, like the orange, can hold acid as well as sugar.

In The Godfather, my dad’s favourite movie, oranges take on a different symbolic role. Vito Corleone (please read that name in the voice of a Sri Lankan man doing his best Italian accent, fingers pinched) is out buying oranges when he’s gunned down in the street. He drops a bag of oranges and pulp splatters the ground like blood and guts. My school’s speaker would’ve probably done a jig at this unrestrained destruction of oranges. Once done, it can’t be undone.

But the film suggests otherwise. Later, Vito recovers. He is not the same, but he’s still powerful, still a father, still Veeeeeto Corrrrleeonaaay. In a film that focuses so much on transformation, you could argue that that the oranges are used to symbolise change, not necessarily destruction. You could. Director Francis Ford Coppola just says they were there to break up the dark visuals.

Gary Soto’s Oranges plays with a similar contrast. Against the sludgy greys of winter, the fruit in his poem blazes like a fire in the dark street, just as it does in The Godfather’s sombre sets. The orange insists on being seen.

I peeled my orange

That was so bright against

The gray of December

That, from some distance,

Someone might have thought

I was making a fire in my hands

Soto’s poem describes a moment when he was twelve, unable to pay for his date’s chocolate bar. I enjoy that in both poems, as well as Wendy Cope’s famous The Orange, oranges represent a memory of intimacy.

Reading these poems, I still wonder if the speaker at that school assembly got it all wrong. She wanted to teach an absolute: once something is done, it can’t be undone. The orange, once peeled, can’t be put back together again. I’ve long stopped watching atheist YouTube videos but I can’t shake the impulse to challenge her thesis.

The orange, even after being peeled, is still an orange. It’s still fragrant, sweet, something to be held and shared. A peeled orange, like a shot Vito Corleone, just exists in a different state. To say it’s ruined is to misunderstand transformation.

Love is no different. It doesn’t vanish just because it’s no longer present in the way it once was. It imprints itself into us, shaping how we touch and taste the world. Once touched, its oil clings to your fingers and you carry it with you long after you've washed your hands.

When my boyfriend visited my family for Christmas, we’d only been dating for a few months. It was December and the kitchen windows were fogged up from cooking steam. He sat laughing with my parents after the meal, our empty plates buried in fruit peels. He’d had an orange. The peel curled on his plate entirely intact, removed in a single piece, unzipped around the middle.

-

Further reading for fans of oranges:

The Foods of Love? Food Gifts, Courtship and Emotions in Long Eighteenth-Century England (doi:10.1017/S0080440123000270)

Citrus: From Symbolism to Sensuality—Exploring Luxury and Extravagance in Western Muslim Bustān and European Renaissance Gardens (doi: 10.3390/arts13060176)

this absolutely bangs, more pls!! oysters??? figs???

This is exactly as delicious as I knew it would be... More!