Someone write a book about this woman

If you caught a glimpse of Minnette de Silva in 1940s London, you would've remembered it for the rest of your life.

If you had caught a glimpse of Minnette de Silva in 1940s London, you would have remembered it for the rest of your life. Many did. At the Architectural Association, where she studied, fellow students recall her sweeping through the halls with a trail of admirers in her wake. A small fan club of fellow students carried her books and shawls like a royal entourage. The librarian recalls de Silva’s beflowered hair, bangles and glittering saris, saying “her visits to the library always caused a little flutter.”

De Silva was famous for her magnetic presence. Yet behind the glamour was a mind brimming with revolutionary ideas both in architecture and in politics. She came of age in Sri Lanka just as colonialism was starting to fray. As she watched her country fight for independence from British rule, she decided that its architecture should too. Her socially conscious, eco-sensitive housing designs were ahead of their time in the 1940s, pioneering sustainable techniques we still use today.

The first time I read about Minnette de Silva I felt like I’d stumbled across a character from a novel. It was an article about modernism, a minor reference to an obscure Sri Lankan architect who worked alongside local craftswomen. With a mountain of urgent tasks waiting, I did the only logical thing I could do: I fell down a Google rabbit hole.

The more I read, the more I was surprised that a biography about de Silva didn’t exist. She ran her own architecture firm in a newly independent country at a time when most women weren’t even allowed to practice. She discussed peace with Picasso, straightened Indira Gandhi’s hair, and kept a box of love letters David Lean wrote her when he filmed The Bridge on the River Kwai in Sri Lanka. With so much intrigue in her personal life and a groundbreaking professional legacy, I was shocked that the most substantial accounts of her life were either flat or outright creepy.

Too often, de Silva has been flattened into a caricature – an ‘exotic princess’ in the press, a pining love interest in a published Le Corbusier fanfic (more on this later), or forgotten entirely. Fellow architect David Robson once described her as “a cross between Don Quixote and Louisa May Alcott’s Jo March.” A woman like that would fit great in the driver’s seat of a book. Her place in the spotlight is still long overdue.

Long before London, de Silva was a wild, clever girl growing up in the misty hills of Kandy, Sri Lanka. Their family home was a main character factory. Her mother fought fiercely for all Sri Lankan women to get voting rights, something they accomplished before France, Italy and Japan. Her father, an anti-colonialist and lawyer, insisted that his girls should debate politics at mealtimes. Under these conditions, the de Silva children learned that change wasn’t just something you could ask for. You had to fight for it, and if they didn’t give it to you, you had to build it yourself.

What Minnette de Silva wanted to fight for more than anything was to be an architect. She persuaded a wealthy uncle to fund her studies in Bombay where she was the only female student among 40 men. When she joined an anti-colonial march, the university demanded a letter of apology. Instead, de Silva chose to accept expulsion.

Although that feels like the end of a Netflix pilot episode, de Silva’s choice to be expelled was pivotal. It was the collision of architecture and activism, two forces she refused to separate. Instead of bowing her head and resuming her studies, she left Bombay and enrolled at the Architectural Association in London. Her fellow students describe her as a tropical bird (hm…) among grey-suited men.

Postwar London was a grey blur of rations and rubble. De Silva took a cheap attic flat in Savile Row, black-out paper still clinging to the windows from bygone air raids. She studied by day and attended fashionable parties at night, moving into the orbits of some of architecture’s best minds. On a trip to Paris, she met famous architect Le Corbusier. High above the city in his rooftop studio, he shocked everyone by breaking his own English language embargo just to chat with her.

This marked the beginning of a friendship that would span decades. In 1948, both de Silva and Le Corbusier found themselves at a fiery gathering aimed at curbing the Western nuclear arms race. De Silva stepped up to the microphone before a packed hall of 600 delegates – including Aldous Huxley, Pablo Picasso, and Pablo Neruda – to deliver a speech. Her words landed with such an electrifying impact that historian Gillian Darley called the crowd’s applause “monstrous.”

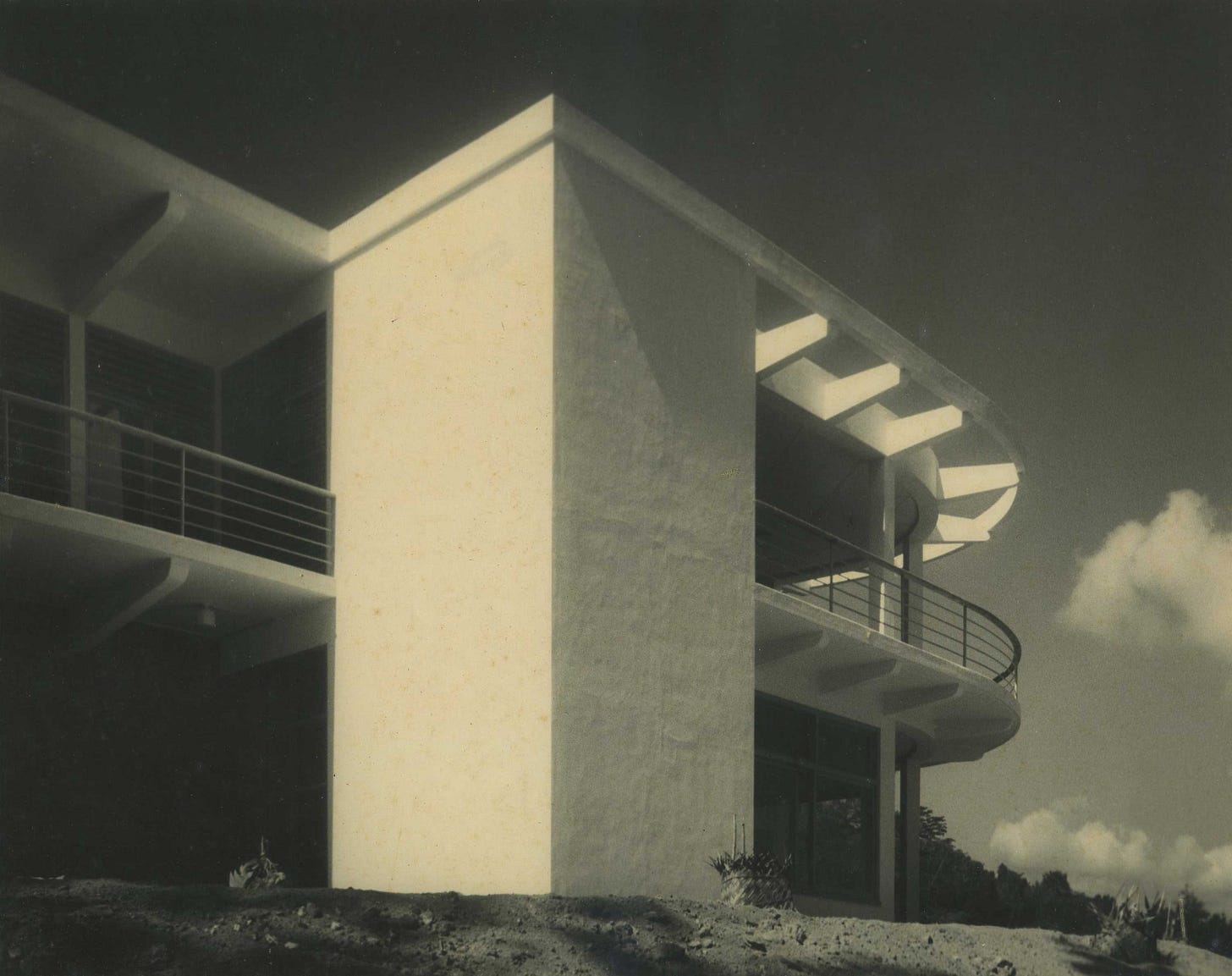

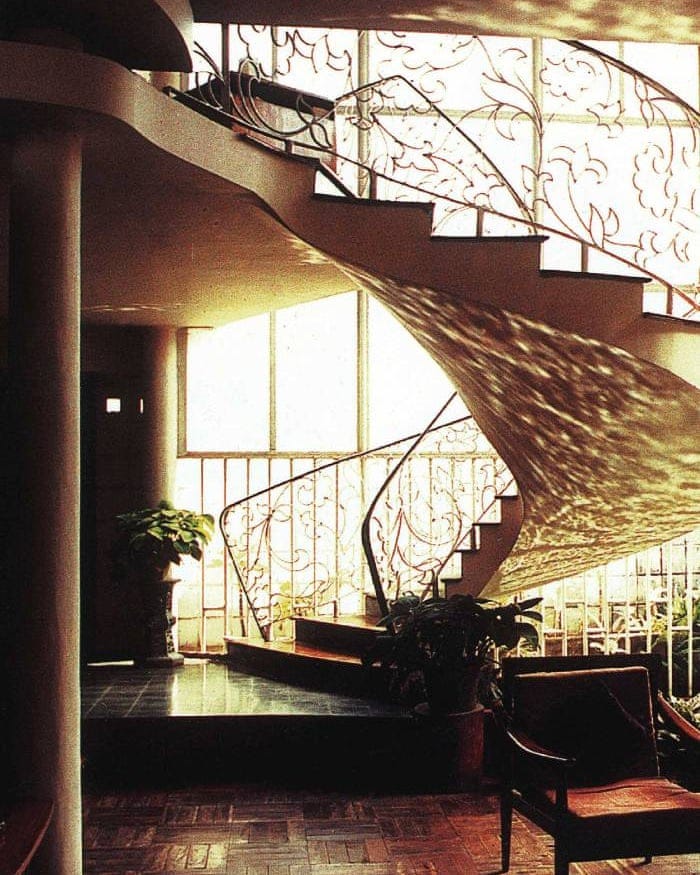

That same year, Sri Lanka threw off its colonial chains. De Silva’s father urged her to fly home and help (literally) build the country. Her first project was the Karunaratne House, the first home ever designed by a woman in Sri Lanka. It was a tropical bungalow folded into the green hillside with swirling staircases and open terraces. She used modern glass blocks and concrete but collaborated with local craftspeople for their weaving and terracotta tile-work.

This use of ancient, local techniques meant de Silva’s buildings became a collaboration across time and class. Through her work and fierce advocacy, local craftspeople, particularly women, weren’t only honoured. They were employed.

Where others might have bulldozed the hillside to fit their housing projects, de Silva let the hills shape her design. The north-facing façade’s huge windows and deep balconies allowed for natural ventilation to cool the interior. The south-facing façade’s solid walls shielded the house from the tropical heat. These eco-sensitive methods are still considered best practice today.

De Silva’s public housing work was just as groundbreaking. She was tasked to create affordable housing for a diverse ethno-religious community of public servants. Before designing the building, she surveyed all its future residents, working with them to best cater to their needs. This participatory design model, common now, was radical back then. She believed that architecture should be democratic, shaped by the lives of those who lived in it, not imposed from the top down.

Working in a male-dominated field, de Silva had no choice but to be tough. Her qualifications were routinely challenged, even by those who hired her. Once, a contractor refused to proceed until her plans were validated by another engineer. At first, people admired how she could hold her own with teams of workmen. Before long, that confidence got de Silva labeled as “difficult.”

In the 1960s, her successor’s work began to eclipse her own. A Colombo-based architect named Geoffrey Bawa rose to prominence in the 1960s with a style that de Silva had pioneered a decade earlier. While Bawa had the benefit of private wealth, influential patrons and institutional support, de Silva struggled to maintain commissions and was often sidelined in architectural circles. Bawa became known as the pioneer of Tropical Modernism. The fact that he’s remembered while she’s forgotten says more about power than talent.

“I was dismissed because I am a woman,” de Silva later said. “I was never taken seriously for my work.” Her commissions dried up in the 60s and 70s. She quickly found herself shut out of the very profession she had helped shape.

What de Silva called Regional Modernism is now called Critical Regionalism, attributed to Kenneth Frampton. Many of her buildings lie in ruin and her legacy remains overshadowed by Bawa’s. Her ideas survive but they’ve been severed from her name.

Even now, she’s often remembered through the most condescending lens possible. A Guardian piece calls her an “exotic oriental princess.” An Independent obituary focuses on her “fragile, slim Asian beauty.” Although her wit and glamour were part of her charm, this exoticised othering is a sad way to refer to one of the pioneering minds of 20th century architecture. We don’t talk about Picasso as a 5'4" little Spanish prince.

In the novel Plastic Emotions, de Silva is fictionalised as a woman pining for Le Corbusier, a man 30 years her senior, in a romance she explicitly denied ever happened. For someone who never married (she said that husbands are only good for carrying one’s bags), it feels disappointing that this is how she’s remembered. David Robson, an architect who knew her personally, wrote, “Plastic Emotions constitutes a slanderous assault on Minnette’s person and reputation which serves only to slake the ambitions of its author. Minnette deserves better.”

Minnette de Silva deserves a respectful, well-rounded portrayal on her own terms, not as a pining love interest, a footnote in Bawa’s biography or a sad old lady who died in a crumbling house. Her life has all the ingredients of a sweeping novel or a lush biopic: the politics of independence, the chaos of postwar London, the battle of a pioneering woman in a man’s world.

I would love to see a writer share de Silva’s story, not just the lines she drew on paper but the lines she crossed and redrew in London, Bombay, Kandy. Spotlight her work but her politics too, a rounded, human portrayal. Share the life of a woman you wish you could’ve had a drink with. A story where Minnette de Silva gets her rightful place not behind a famous man but at the drafting table, sleeves rolled up, flowers in her hair, building a fairer world.

Thanks for reading! Here are some extra photos and sources for your curiosity…

https://thinkmatter.in/2020/05/22/book-plastic-emotions-reviewed-by-david-robson/

https://www.architecture.com/about/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/remembering-minnette-de-silva

https://www.wmf.org/projects/minnette-de-silva-project

I love the subject area as a woman from Sri Lanka. I am new to Substack but trying to write about Sri Lanka. Your writing is amazing.

This is incredible! Yes we need to have her story giving her all the respect for all that she’s done and for the life she’s fought to live.