On Dating Writers

Looking to literary couples (Plath, Didion, Nabokov, Hemingway) and their various juicy scandals to answer the question: Should you date a writer?

Ted Hughes is arguably most famous for getting his surname repeatedly chipped off Sylvia Plath’s gravestone. Although he was a Poet Laureate with an OBE, he’s better known these days as the callous adulterer who butchered his late wife’s work after her suicide. He destroyed the final volume of her journals, taking his editorial cleaver to her poetry and even censoring her letters to her mother. People still debate about the motivations behind this censorship, but what’s clear is that Plath and Hughes are far from the only writer-writer couple with a volatile backstory and a volcanic finale.

When I was dating last summer, I had a rule: No writers. This had nothing to do with Ted Hughes or his ilk, and was entirely based on a stereotype. I pictured some guy in rolled jeans and a vintage jacket forcing the prisoners at his open mic show to read his political zine. Ankles out. Baby Guinness. Murakami collection waiting for him at home with pristine spines.

Prejudiced as it was, my rule had a little bit of merit. I’d seen too many clever women get sucked into the orbit of this exact species of boyfriend. Soon their own manuscripts were set aside so they could proofread his Bukowski-inspired poetry. I refused to let it be me. If I could sniff Le Labo on a man, my biological reflexes kicked in and sent me sprinting to the hills (on a bike-hostile path to avoid his pursuit).

The expectation that a writer’s genius must be nurtured by a partner, usually a woman, has been a recurring trope in history. There isn’t a better case study for this than in the life of Véra Nabokov. A published writer herself, she’s instead gone down in history as literature’s most loyal sidekick.

Véra met Vladimir Nabokov in 1923, on a bridge over a chestnut-lined canal. Wearing a black harlequin mask from the springtime ball they’d just attended, she recited his poems as they wandered the streets of Berlin. He fell in love with his words in her mouth. They married two years later.

Instead of pursuing her own writing, Véra quickly fell into the role of Vladimir’s helping hand. She was his cook, bodyguard, typist, housekeeper, agent, babysitter, chauffeur, editor, stamp-licker and secretary. Many suspected that Véra had a hand in the writing itself, with some conspiracists even claiming she was the true author of her husband’s work. A rare woman in the male-dominated field of authorship debates!

“It’s as if in your soul there is a preprepared spot for every one of my thoughts,” Vladimir Nabokov wrote. His smart, ambitious wife was a vessel, one he spoke of with adoration at times and referred to as his “assistant” at others. Although harsh, the label was fair. She did everything for him, including saving his manuscript of Lolita from the fire.

For many literary superstars, talent alone wasn’t enough. Their success might never have been possible without steadfast human capital. Véra’s devotion ensured her husband’s literary immortality but it also left her own creative voice adrift. For all we know, she seems happy with that choice.

When my friends offer to set me up with their writer pals, Véra’s isn’t the fate I fear. I don’t think these guys want a woman to stay at home so they can focus on their Substacks. Less than being overshadowed, what’s always spooked me about writer-writer couples was the immense potential for envy. A textbook case of this was Ernest Hemingway.

Hemingway, who only had two wives fewer than Henry VIII, started an affair his soon-to-be third in 1936. She was a sharp-pencilled war correspondent named Martha Gellhorn, sent to Spain to report the civil war. They were both staying at the Hotel Florida when they began their fling. Nighttime air raid sirens sent guests scrambling to the basement for safety, and Gellhorn was spotted with dishevelled hair, wearing a married Hemingway’s coat over her pyjamas. They were wed four years later.

While Gellhorn reported the Invasion of Normandy from the front lines, Hemingway watched from afar, using binoculars. He mocked her dedication, sometimes sabotaging her work. He wrote, “Are you a war correspondent or a wife in my bed?” Seemingly he was unhappy to let her be both.

Their fights escalated. One ended with Hemingway slapping Gellhorn in the front seat of his prized Lincoln Continental, so she drove it slowly into a tree.

After their divorce, Gellhorn refused to discuss her ex-husband. “I’ve been a writer for over 40 years,” she said. “Why should I be merely a footnote in his life?” Through her own grit, Gellhorn avoided being an “assistant” like Véra Nabokov. It cost her her marriage, but that was clearly a price she was happy to pay.

In retrospect, I’m not sure how much of my fear of dating a writer was, to put it bluntly, wanky. I’m not Martha Gellhorn. The open mic guys aren’t Ernest Hemingway. Far from being jealous of my D-Day beach reporting, the worst they could manage was envy my small wins in lit mags. There wasn’t a future where I was vengefully crashing anyone’s Lime Bike.

My mindset felt outdated, in clear need of a shift. I’d taken my fears from other people’s love stories. I could take a bit of hope from them too.

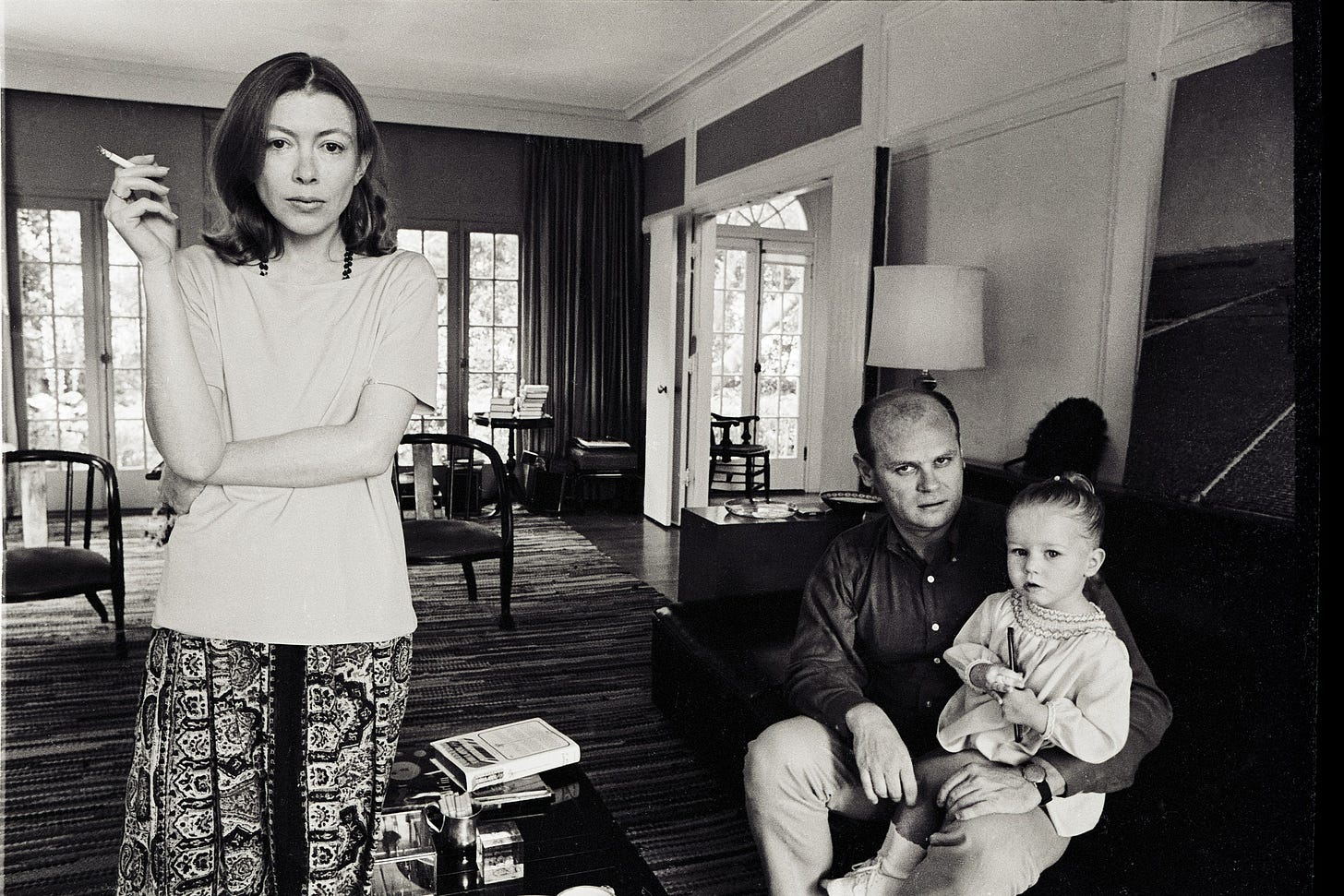

Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne work as a compelling counterpoint to the idea of a toxic writerly relationship, sharing 40 years of literary and marital partnership. They were each other’s collaborators, both on newspaper columns and screenplays, and their manuscripts often bear one another’s fingerprints.

“At dinner she sits and talks about her book, and I talk about mine,” Dunne says. “I think I’m her best editor, and I know she’s my best editor.”

You can actually see him in that famous picture of her smoking in her living room. Although he’s frequently cropped out (including by me, sorry John), he’s right there next to her, holding their daughter.

The New York Public Library recently displayed the couple’s archive, 336 boxes of drafts, letters and notes. The collection makes clear how much they influenced each other’s work. In Didion’s words, “Because we were both writers and both worked at home our days were filled with the sound of each other’s voice.”

That sounds a lot like my apartment this afternoon.

I’m on the sofa with my boyfriend. We’re sitting across from each other, laptops open. For the past hour, we’ve been staring at the same document, my manuscript, as sunlight drifts slowly across the floor. We’re talking through a plot problem, tossing ideas back and forth. By the time we solve it, the light has reached the orchids by the table.

Against my own rules, I’m dating a writer. One whose ankles are safely stored behind appropriate-length jeans, but a writer nonetheless.

At first I was cagey about my writing. Sometimes I’ll see a man’s eyes light up when they hear I’ve been published, only for the candle to flicker out the second they learn it’s a short fairytale or a poem about frogs. I’d learned to anticipate the polite nod followed by the slow conversational drift toward their own creative genius.

I can safely say through the window frame of hindsight that I had nothing to be worried about. My now-boyfriend read my frog poem on the London Overground and laughed in the right place. It was the first piece of mine he read, though he’s since read many more. He’s my first reader and best editor, someone who’s urged me to submit my work to places I always thought were too good for me.

Didion and Dunne being each other’s “best editor”s stands to reason. I love reading my boyfriend’s work. Whenever you read your partner’s first draft, you get a front-row seat to how they think. Editing is an extension of emotional intimacy.

Once, my boyfriend flagged a single sentence and said, “This feels like you're trying to sound like someone else.” He was right. No one else would’ve caught that, but there’s no hiding from someone who knows you this well.

Sometimes he’ll write in the margins, This is great. Keep this. Other times he’ll say Hmm, this contradicts what you’ve written 2 paragraphs up. Whether compliments or critiques, these little Google Docs annotation bubbles read to me like love notes.

History tends to spotlight the literary couples who imploded – the infidelities, the bruised egos, the manuscripts fed to flames. Conflict makes for better copy but more successful partnerships exist too. The world is full of Didions and Dunnes. Zadie Smith and Nick Laird edit each other’s work and co-write children’s books in between novels. Ransom Riggs and Tahereh Mafi were married in a library, their bouquets threaded with book pages.

These aren’t just exceptions to the rule but evidence that love and literature don’t have to compete. I'm starting to see that the right collaborator doesn’t eclipse your voice. They help you hear it more clearly.

-

Some notes: Sorry to all my male writer friends for the stereotypes! I’ve grown and recovered. Sort of. Also I don’t want to put Joan Didion and John Dunne’s relationship on a pedestal in this piece. Also Martha Gellhorn was far from an angel. Use this space to imagine all the disclaimers you can think of. Also, blehhhhhhh

I chatted with a writer friend a few months ago, and she was like “I couldn’t date another writer. Too many neuroses” in the kitchen was her reasoning, basically. I don’t know if I disagree.

I think two writers can make it work IF they are both working on becoming the most emotionally mature, stable versions of themselves. Two tortured artists or two perfectionist writers who smart at the first sign of criticism or offer feedback tinged with envy or jealousy…yeah, that’s not gonna work out.

My boyfriend has some interests in specific kinds of writing, but he’s mostly into other forms of art like drawing and filmmaking. It works well for us. He’s creative enough to understand my passions (and I can support his) without being so steeped in my world, while I also can nurture his passions. I have writers groups and other people I can turn to if I want in-depth feedback on my writing.

Really enjoyed reading this—it kept me hooked the whole way. Thanks for sharing!🌻