A stone goddess watches over the door of the tobacco shop across my road. The flowers framing her look like they’ve been coaxed into bloom rather than carved from sedimentary rock. The iron balcony railings curl like ferns on the sun-toasted orange facade, and my neighbours lean over them to vape. You can smell it from the street: bubblegum. They probably got it downstairs. Inside this casual slice of magic, built in 1901, you can buy a scratch card for a euro or an Elf bar for five.

A lot of European cities exist like this, with fairytale-like architecture nestled between corner shops and laundromats. Many of these buildings follow a dreamlike, swirling art style that feels like it belongs in a fantasy novel: Art Nouveau. Just like modern fantasy, it has its roots in the late Victorian Era.

By the later half of the 19th century, the Second Industrial Revolution was in full swing. Progress clattered along with innovations in assembly lines and cheap mass production. Workers were packed into crowded urban centres to toil in dirty, dangerous factories.

“Fantasy arose as a reaction to the development of industry and war in the 19th century,” says The Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s primer on fantasy environmentalism. “Saving nature from human aggression and reconnecting with it are major issues of the genre.”1

Around the same time, a new movement appeared, known as Art Nouveau (also called Jugendstil in German, Modernisme in Catalan, and Noodle Style by Victorian losers who hated fun). It lasted from roughly 1890 to the start of World War One.

The ideological parentage of Art Nouveau has its roots in Britain, in the designs of William Morris. His championing of craftsmanship in the face of industrialisation as well as his foliage-based designs helped shape the Arts and Crafts movement, which would then go on to influence Art Nouveau. He was also one of the 19th-century novelists who helped establish the modern fantasy genre (cheers Will) (very productive).

Morris, an active and vocal socialist (again, very productive), called the conditions created by the Industrial Revolution a “devilish capitalistic botch and an enemy of mankind.” He longed for the Middle Ages when craftsmen made objects that were both beautiful and useful.

Although “Arts and Crafts” now has connotations of glitter glue, take the name as literally as you can — Morris wanted the crafts to prioritise artistry and craftsmanship. Instead of factory-produced junk, he wanted artisans to lead the entire creative process from design to creation. He preferred organic dyes over chemical ones, natural materials over the industrial.

Art Nouveau was the conceptual nephew of Arts and Crafts. It took Morris’ ethos into the modern age, using new technologies like cast iron to create winding vine-like structures. It borrowed from Japanese woodblock prints, Islamic geometric patterns, and the elegant chaos of nature.

The same era that birthed Art Nouveau saw a resurgence of fairy tales. With their roots in pre-industrial times, they offered an escape from the machine-driven present. Strap in, I’m about to start listing things.

Andrew Lang’s fairy books (1889 and 1910), Oscar Wilde’s fairytales (1888 and 1891) and the first appearance of Peter Pan (1904) all fed this hunger for magic. Other notable works in this timeframe include The Book of Dragons by Edith Nesbit (1899), The Wood Beyond the World by William Morris (1894), Lilith by George MacDonald (1895) and Puck of Pook's Hill by Rudyard Kipling (1906).

A flood of lavishly illustrated fairytale editions released when the copyright for Grimms’ Fairy Tales expired in 1893. Some of those tales (Rumpelstiltskin, The Fisherman and His Wife) warned against unchecked greed, a fitting theme for the era of rampant industrialisation.

Art Nouveau artists brought these fantasies to life, with many designing the covers and inserts for the books listed above. Aubrey Beardsley illustrated Le Morte d’Arthur (1893) with eerie knights and robed witches, while Arthur Rackham’s forests, fairies and gross little imps became reference points for fantasy art today.

Even outside the storybooks, fantasy and myth played a noticeable hand in Art Nouveau. Antoni Gaudí’s Casa Batlló has a roof of ceramic dragon skin, shimmering like a hoard of jewels. An undulating wave of scales rises as if the roof might rear up and dive back into the earth, huffing scalding steam. It nods to the legend of Saint George (Sant Jordi), the dragon-slayer. Every year, the facade blooms with red roses to celebrate his festival.

René Lalique’s jewellery features fantastical influences too. He made pendants of tiny, glass-bodied fae, wrapped in wings decorated with pansies and blackberries. Similar to stained glass, his translucent enamel gleams when lit from behind. In keeping with Morris’ ideology, this is a long-lost Medieval technique, revived to create something beautiful and usable.

Although it’s easy to pinpoint key examples like this (there was a whole exhibition on fantasy themes in Art Nouveau2), I can’t find any literature crediting fantasy as a strong influence on the style as a whole. I can, however, find evidence that Art Nouveau influenced fantasy.

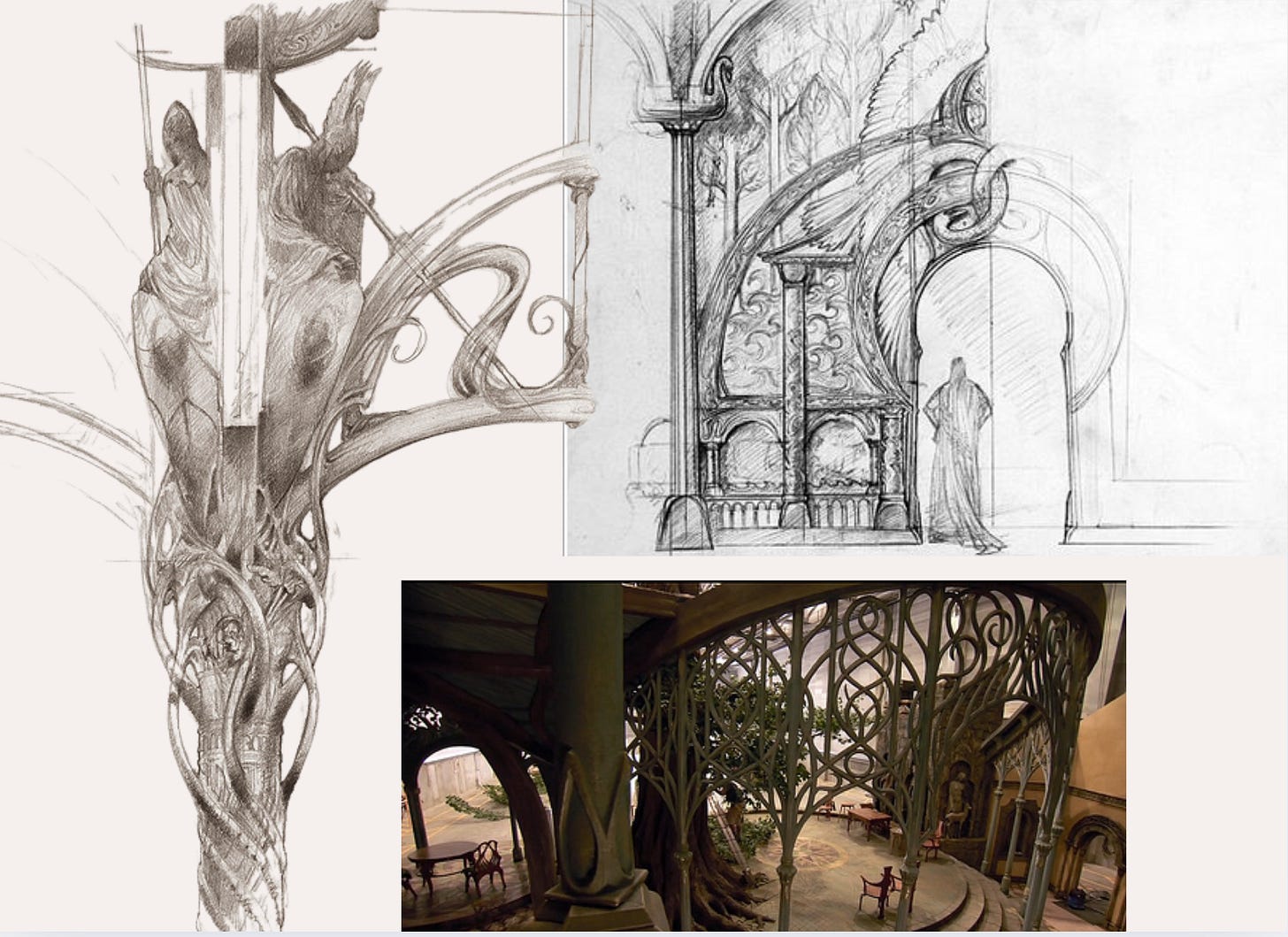

Illustrators John Howe and Alan Lee, chief conceptual designers for Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings films, drew from Art Nouveau to shape Rivendell. As guardians of the natural world, it makes sense that elves would live in architecture that celebrates nature. For the record, industrious dwarves prefer Art Deco.

Another example that I can’t find anything about online is Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle. The fictional world of Ingary is covered in Art Nouveau details with curls of steel and soaring stained glass windows. Its real-life inspiration, the French town of Colmar, is full of twisting Art Nouveau stonework wedged beside half-timbered Alsatian shops. Ingary’s aesthetics makes sense with the movie’s vaguely Edwardian setting but I think the sprinkles of Art Nouveau enhance the story’s themes.

Its tendrils of influence are most obvious in Sophie’s hat shop. She works under the amber glow of a tulip-shaped gas lamp, hanging her finished hats on a stand that curls like a steel vine. Plaster stems snake up a green wall, sprouting pink rosebuds. Above the door, a half-rose window fans out in curling iron petals.

As Sophie steps into town, she drifts through a landscape of vivid Edwardian signage, looping iron bannisters, and swirling facades. She coughs as a train belches black soot. The trains are driven by the same technological progress that churns out fighter planes and warships, whose arrival is marked by an ever-encroaching smog.

When Howl’s castle, just as smoky and mechanical as any warship, waddles through the rolling Alpine fields, the sheep don’t blink. Despite the castle’s wheezing pipes and clanking joints, it treads lightly. It’s modern, mechanical, yet strangely organic with its face and chicken legs. While the castle’s far from the aesthetics of Art Nouveau, it follows the formula: cutting-edge technology emulating the wild.

It’s easy to see how fantasy artists have taken inspiration from Art Nouveau. Whenever I click through the images of buildings I want to visit, my notebook fills up with ideas. You can’t look at Casa Batlló without imagining a city built atop the scaly husk of an ancient dragon, its spines repurposed as fortifications. The entrance of Victor Horta’s Hôtel Tassel conjures an elven palace where vines shift to rearrange rooms with the seasons. The Grand Palais could be an observatory where scholars track moving constellations. Even Lalique’s pendants become captured fairies, worn as a status symbol or to enhance the magic of their wearers. Art! Nouveau!

I have a great big list of Art Nouveau buildings I want to visit one day. You could easily write a fantasy novel about any of them. On the off-chance of inspiring a fantasy writer, here are 5 of the prettiest places from my list…

Maison Saint-Cyr: A slender, eerie townhouse with wrought-iron spirals. Perfect home for a ghostly artist.

Casa Galimberti: A stunning floral apartment building in Italy. A great base for witches who openly practice botanical magic.

Palau de la Música Catalana: A jewel-toned concert hall with stained-glass skylights. You could picture some concerto-themed magic or a high-stakes magical masquerade.

École de Nancy Museum: Once a private mansion, now filled with curving wood and floral glass. If I were a sorcerer, I’d want my home to look exactly like this.

Villa Demoiselle: Imagine a fantasy novel set in an enchanted champagne house in the French hills! What’s hiding in the cellar?

Perhaps it makes sense that I’m dreaming of fantasy worlds amidst yet another Industrial Revolution, the 4th, marked by AI and mobile phones. Just like William Morris, we’re seeing people’s labour be exploited in service of creating diabolical tat. Companies like Shein use sweatshops to churn out copies of more expensive artisanal designs. Mugs are mass-produced with visible dents and brushstrokes to emulate an artist’s touch.

I like to believe that Art Nouveau appeals to modern fantasy fans not just because of the elven aesthetic but also the ethos. Fantasy is a genre that often warns against industrialisation. The ‘old ways’ are often valued in the face of destructive progress but they’re also challenged, questioned and innovated upon.

In Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, Strange draws on magic’s natural, untamed past to pull it forward. Instead of advocating for a return to England’s folkloric history, teeming with wicked creatures, the narrative asks which parts of the past are worth reviving and how they should evolve. In the same way, Howl’s Moving Castle doesn’t paint all technology as evil, only the kind that dehumanises.

It’s fun walking down the street, thinking about the era that birthed my favourite architectural style and my favourite genre. There’s plenty to learn from from both, especially in the midst of our own Industrial Revolution. Like Art Nouveau, fantasy resists the idea that progress must come at the cost of wonder.

Notes From Sitara:

This was so much fun to research and write! Please reach out to me if you have any corrections you’d like me to make (I’d be glad to!) or if you just want to discuss the topic. You might also like these posts…

How Fantasy Fuelled 60s Counterculture

It’s 1965. Students in army surplus jackets pass joints in their dorm while a wobbly Bob Dylan record plays. The war in Vietnam is escalating. Draft cards are arriving in mailboxes, friends and neighbours are disappearing. Among the Xeroxed anti-war leaflets and college textbooks, there’s a cheap, bright-red paperback being passed from hand to hand. It’…

Why Everyone "Sweats Profusely" in Novels

I was reaching the end of my fantasy manuscript’s six-thousandth draft. My leading man, a spoiled prince ill-equipped for anything more taxing than a pub crawl, was losing a fight. We were equally exhausted, him in a burning palace by the sea, me in the coffee shop across the road from my flat. Smoke was filling his lungs, burning his skin. His vision w…

For further reading, please check out the following sources…

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/art-nouveau-an-international-style

https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/bulletin/207/the-arts-and-crafts-movement-at-the-end-of-the-wor

https://fantasy.bnf.fr/en/explore/advocating-defense-nature

https://g.co/arts/2Y6GCjwis8d614Y86

Thank you for writing and sharing this piece! Have you read, "Anime Through the Looking Glass?" I think you'd enjoy it since it covers how iconic films were social commentary on war and environmentalism. Especially among Ghibli Studio's work!

If you haven’t done so already, check out the Tolkien did himself. They have a distinctive art nouveau look to them.